The Inca were a conquering society, and their expansionist assimilation of other cultures is evident in their artistic style. The artistic style of the Inca utilized the vocabulary of many regions and cultures, but incorporated these themes into a standardized imperial style that could easily be replicated and spread throughout the empire. The simple abstract geometric forms and highly stylized animal representation in ceramics, wood carvings, textiles and metalwork were all part of the Inca culture. The motifs were not as revivalist as previous empires. No motifs of other societies were directly used with the exception of Huari and Tiwanaku arts.

Architecture was by far the most important of the Inca arts, with pottery and textiles reflecting motifs that were at their height in architecture. The stone temples constructed by the Inca used a mortarless construction process first used on a large scale by the Tiwanaku. The Inca imported the stoneworkers of the Tiwanaku region to Cusco when they conquered the lands south of Lake Titicaca. The rocks used in construction were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable in the frequent earthquakes that strike the area. The Inca used straight walls except on important religious sites and constructed whole towns at once.

Architecture was by far the most important of the Inca arts, with pottery and textiles reflecting motifs that were at their height in architecture. The stone temples constructed by the Inca used a mortarless construction process first used on a large scale by the Tiwanaku. The Inca imported the stoneworkers of the Tiwanaku region to Cusco when they conquered the lands south of Lake Titicaca. The rocks used in construction were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable in the frequent earthquakes that strike the area. The Inca used straight walls except on important religious sites and constructed whole towns at once.

The Inca also sculpted the natural surroundings themselves. One could easily think that a rock along an Inca trail is completely natural, except if one sees it at the right time of year when the sun casts a stunning shadow, betraying its synthetic form. The Inca rope bridges were also used to transport messages and materials by Chasqui running messengers. The Inca also adopted the terraced agriculture that the previous Huari civilization had popularized. But they did not use the terraces solely for food production. At the Inca tambo, or inn, at Ollantaytambo the terraces were planted with flowers, extraordinary in this parched land.

The terraces of Moray were left unirrigated in a desert area and seem to have been solely decorative. The Inca provincial thrones were often carved into natural outcroppings, and there were over 360 natural springs in the areas surrounding Cusco, such as the one at Tambo Machay. At Tambo Machay the natural rock was sculpted and stonework was added, creating alcoves and directing the water into fountains. These pseudo-natural carvings functioned to show both the Inca's respect for nature and their command over it.

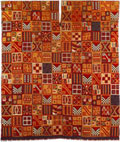

Inca tunicInca officials wore stylized tunics that indicated their status. The tunic displayed here is the highest status tunic known to exist today. It contains an amalgamation of motifs used in the tunics of particular officeholders. For instance, the black and white checkerboard pattern topped with a red triangle is believed to have been worn by soldiers of the Inca army. Some of the motifs make reference to earlier cultures, such as the stepped diamonds of the Huari and the three step stairstep motif of the Moche. In this royal tunic, no two squares are exactly the same.

Inca tunicInca officials wore stylized tunics that indicated their status. The tunic displayed here is the highest status tunic known to exist today. It contains an amalgamation of motifs used in the tunics of particular officeholders. For instance, the black and white checkerboard pattern topped with a red triangle is believed to have been worn by soldiers of the Inca army. Some of the motifs make reference to earlier cultures, such as the stepped diamonds of the Huari and the three step stairstep motif of the Moche. In this royal tunic, no two squares are exactly the same.

Cloth was divided into three classes. Awaska was used for household use and had a threadcount of about 120 threads per inch. Finer cloth was called qunpi and was divided into two classes. The first, woven by male qunpikamayuq (keepers of fine cloth), was collected as tribute from throughout the country and was used for trade, to adorn rulers and to be given as gifts to political allies and subjects to cement loyalty. The other class of qunpi ranked highest. It was woven by aqlla (female virgins of the sun god temple) and used solely for royal and religious use. These had threadcounts of 600 or more per inch, unexcelled anywhere in the world until the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century.

Aside from the tunic, a person of importance wore a llawt'u, a series of cords wrapped around the head. To establish his importance, the Inca Atahualpa commissioned a llawt'u woven from vampire bat hair. The leader of each ayllu, or extended family, had its own headdress.

In conquered regions, traditional clothing continued to be worn, but the finest weavers, such as those of Chan Chan, were transferred to Cusco and kept there to weave qunpi. (The Chimú had previously transferred these same weavers to Chan Chan from Sican.)

The wearing of jewellery was not uniform throughout the empire. Chimú artisans, for example, continued to wear earrings after their integration into the empire, but in many other regions, only local leaders wore them.

Ceramics were for the most part utilitarian in nature, but also incorporated the imperialist style that was prevalent in the Inca textiles and metalwork. In addition, the Inca played drums and on woodwind instruments including flutes, pan-pipes and trumpets made of shell and ceramics.

Ceramics were for the most part utilitarian in nature, but also incorporated the imperialist style that was prevalent in the Inca textiles and metalwork. In addition, the Inca played drums and on woodwind instruments including flutes, pan-pipes and trumpets made of shell and ceramics.

The Inca made beautiful objects of gold. But precious metals were in much shorter supply than in earlier Peruvian cultures. The Inca metalworking style draws much of its inspiration from Chimú art and in fact the best metal workers of Chan Chan were transferred to Cusco when the Kingdom of Chimor was incorporated into the empire. Unlike the Chimú, the Inca do not seem to have regarded metals to be as precious as fine cloth. When the Spanish first encountered the Inca they were offered gifts of qunpi cloth.

The Inca did not possess a written or recorded language as far as is known, but scholars point out that because we do not fully understand the quipu (knotted cords) we cannot rule out that they had recorded language. Like the Aztec, they also depended largely on oral transmission as a means of maintaining the preservation of their culture. Inca education was divided into two distinct categories: vocational education for common Inca and highly formalized training for the nobility.

The Incan religion was pantheist (sun god, earth goddess, corn god, etc.). Subjects of the empire were allowed to worship their ancestral gods as long as they accepted the supremacy of Inti, the sun god, which was the most important god worshipped by the Inca leadership. Consequently, ayllus (extended families) and city-states integrated into the empire were able to continue to worship their ancestral gods, though with reduced status.

The Incan religion was pantheist (sun god, earth goddess, corn god, etc.). Subjects of the empire were allowed to worship their ancestral gods as long as they accepted the supremacy of Inti, the sun god, which was the most important god worshipped by the Inca leadership. Consequently, ayllus (extended families) and city-states integrated into the empire were able to continue to worship their ancestral gods, though with reduced status.

Much of the contact between the upper and lower classes was religious in nature and consisted of intricate ceremonies that sometimes lasted from sunrise to sunset.

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine. They performed successful skull surgery. Coca leaves were used to lessen hunger and pain, as they still are in the Andes. The Chasqui (messengers) chewed coca leaves for extra energy to carry on their tasks as runners delivering messages throughout the empire. Recent research by Erasmus University and Medical Center workers Sewbalak and Van Der Wijk showed that, contrary to popular belief, the Inca people were not addicted to coca. Another remedy was to cover boiled bark from a pepper tree and place it over a wound while still warm. The Inca also used guinea pigs not only for food but for a so-called well-working medicine.

The Inca believed in reincarnation. Those who obeyed the Incan moral code — ama suwa, ama llulla, ama quella (do not steal, do not lie, do not be lazy) — went to live in the Sun's warmth. Others spent their eternal days in the cold earth.

The Inca also believed in mummifying prominent personages. The mummies would be provided with an assortment of objects which were to be taken into the pacarina. Upon reaching the pacarina, the mummies or mallqui would be able to converse with the area's other ancient ancestors, the huacas. The mallquis were also used in various rituals or celebrations. The deceased were generally buried in a sitting position. One such example was the 500-year-old mummy “Juanita the Ice Maiden”, a girl very well-preserved in ice that was discovered at 20,000 feet, near the summit of Mt. Ampato in Southern Peru. Her burial included many items left as offerings to the Inca gods.

The Inca practiced cranial deformation. They achieved this by wrapping tight cloth straps around the heads of newborns in order to alter the shape of their still-soft skulls. These deformations did not result in brain damage. Researchers from The Field Museum believe that the practice was used to mark different ethnicities across the Inca Empire.

Around 200 varieties of Peruvian potatoes were all first cultivated by the Incas and their predecessorsIt is estimated that the Inca cultivated around seventy crop species. The main crops were potatoes, sweet potatoes, maize, chili peppers, cotton, tomatoes, peanuts, an edible root called oca, and grains known as quinoa and amaranth. The many important crops developed by the Inca and preceding cultures makes South America one of the historic centers of crop diversity (along with the Middle East, India, Mesoamerica, Ethiopia, and the Far East). Many of these crops were widely distributed by the Spanish and are now important crops worldwide.

Many varieties of Peruvian maize (corn) were well-known to the Incas for centuriesThe Inca cultivated food crops on dry Pacific coastlines, high on the slopes of the Andes, and in the lowland Amazon rainforest. In mountainous Andean environments, they made extensive use of terraced fields which not only allowed them to put to use the mineral-rich mountain soil which other peoples left fallow, but also took advantage of micro-climates conducive to a variety of crops being cultivated throughout the year. Agricultural tools consisted mostly of simple digging sticks.

The Inca also raised llamas and alpacas for their wool and meat and to use them as pack animals, and captured wild vicuñas for their fine hair.

The Inca road system was key to farming success as it allowed distribution of foodstuffs over long distances. The Inca also constructed vast storehouses, which allowed them to live through El Niño years in style while neighboring civilizations suffered.

Inca leaders kept records of what each ayllu in the empire produced, but did not tax them on their production. They instead used the mita for the support of the empire.

The Inca diet consisted primarily of fish and vegetables, supplemented less frequently with the meat of cuyes (guinea pigs) and camelids. In addition, they hunted various animals for meat, skins and feathers. Maize was used to make chicha, a fermented beverage.

Extract from http://en.wikipedia.org/