Ollantaytambo constituted an administrative, religious, agricultural and military complex for the IncasThe most powerful figure in the empire was the Sapa Inca ('the unique Inca'). When a new ruler was chosen, his subjects would build his family a new royal dwelling. The former royal dwelling would remain the dwelling of the former Inca's family. Only descendants of the original Inca tribe ever ascended to the level of Inca. Most young members of the Inca's family attended Yachayhuasis (houses of knowledge) to obtain their education.

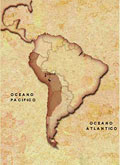

The Tahuantinsuyu was a federalist system which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provinces: Chinchaysuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Qontisuyu (SW), and Qollasuyu (SE). The four corners of these provinces met at the center, Cuzco. Each province had a governor who oversaw local officials, who in turn supervised agriculturally-productive river valleys, cities and mines. There were separate chains of command for both the military and religious institutions, which created a system of partial checks and balances on power. The local officials were responsible for settling disputes and keeping track of each family's contribution to the mita (mandatory public service).

The Tahuantinsuyu was a federalist system which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provinces: Chinchaysuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Qontisuyu (SW), and Qollasuyu (SE). The four corners of these provinces met at the center, Cuzco. Each province had a governor who oversaw local officials, who in turn supervised agriculturally-productive river valleys, cities and mines. There were separate chains of command for both the military and religious institutions, which created a system of partial checks and balances on power. The local officials were responsible for settling disputes and keeping track of each family's contribution to the mita (mandatory public service).

The four provincial governors were called apos. The next rank down, the t'oqrikoq (local leaders), numbered about 90 in total and typically managed a city and its hinterlands. Below them were four levels of administration:

| Level | name | Mita payers |

| Hunu | kuraqa | 10000 |

| Waranqa | kuraqa | 1000 |

| Pachaka | Kuraqa | 100 |

| Chunka | kamayuq | 10 |

Every five waranqa curaca, pachaka curaca, and chunka kamayuq had a intermediary to the next level called, respectively, picqa waranqa curaca, picqa pacaka curaca, and picqa conka kamayoq. This means that the middle managers managed either two or five people, while the conka kamayoq (at the worker manager level) and the apos and t'oqrikoq (in upper management) each had about 20 people reporting to them.

The descendants of the original Inca tribe were not numerous enough to administer their empire without help. To cope with the need for leadership at all levels the Inca established a civil service system. Boys at age of 13 and girls at age of first menstruation had their intelligence tested by the local Inca officials. If they failed, their ayllu (extended family group) would teach them one of many trades, such as farming, gold working, weaving, or military skills. If they passed the test, they were sent to Cuzco to attend school to become administrators. There they learned to read the quipu (knotted cord records) and were taught Inca iconography, leadership skills, religion, and, most importantly, mathematics. The graduates of this school constituted the nobility and were expected to marry within that nobility.

While some workers were held in great esteem, such as royal goldsmiths and weavers, they could never themselves enter the ruling classes. The best they could hope for was that their children might pass the exam as adolescents to enter the civil service. Although workers were considered the lowest social class, they were entitled to a modicum of what today we call due process, and all classes were equally subject to the rule of law. For example, if a worker was accused of stealing and the charges were proven false, the local official could be punished for not doing his job properly.